Generative Perception: Computational Mediation of Umwelten and Epistemic Limits in Biosignal Processing

A conceptual and methodological framework for witnessing without claim as a design ethic for cross-species biosignal interpretation

1. Introduction

We exist within the boundaries of a broader field of phenomena, within a predetermined and narrow perceptual bandwidth. This study explores the technical and perceptual implications of capturing and translating signals from non-human organisms, with a focus on biosignal processing, bioacoustic analysis, and computational perception. The work examines how non-human signals, when processed through human-built systems, expose the boundaries of our perceptive capacity. Informed by creative technology, phenomenology, and animal-computer interaction (ACI), the work addresses representational ethics, algorithmic mediation, and the epistemological limits of cross-species communication through machine learning applications in cetacean research,1 embodiment practices that pursue cross-species perceptual alignment, and analysis of the structural assumptions inherent to sensing technologies.

Signal data is treated here as a record of interaction that encodes its conditions of acquisition. Perception is defined as an active generative process contingent on the operational parameters of its own instrumentation. Alongside this analytic framework, the text references mystical and pre-modern theories of reciprocal perception to establish a conceptual foundation for interrogating the limits and assumptions present in computational sensing technologies.

The paper explains how translation systems shape perception, examines this limit through case studies in bioacoustics and human perception, and proposes a design stance for working with non-human signals.

2. Context of Practice

My earlier work in Hong Kong involved developing interactive installations that translated human biometric activity into generative visual systems. EEG and motion-capture data were used to modulate robotic trajectories and to shape the visual environment of performance works. These projects treated physiological signals as a conduit between the biologically inaccessible and the visually legible.

This work prompted the idea of developing a related system using data from a non-human organism, which then prompted the central question of the present study. If such translation systems are applied to non-human organisms, how many layers of mediation, distortion, and anthropocentric framing become unavoidable? The following section examines this problem.

3. Perception, Mediation, and Situated Knowledge

3.1 Mediation and Phenomenology

When biometric data is collected from human subjects for generative art, mediation happens through a single layer. The activity is registered through devices designed for the human body and translated into a visual or computational output. The translation is still partial, but it remains compatible with the sensory and technical assumptions that informed the design of the apparatus.

When biometric data is collected from non-human organisms, the first layer of distortion arises at the point of capture. These devices, regardless of whether they were originally designed for humans or adapted for animals, work according to human assumptions about detectable activity, registering only what fits their parameters and reflecting the limits of the apparatus rather than the full range of the organism’s behaviour. The subsequent translation of this recording into a visual or computational output compounds this initial loss, as it re-organizes the already incomplete material according to human perceptual and technical conventions. These conditions introduce the risk of ventriloquy, where the apparatus effectively speaks in the animal’s place: because non-human activity is processed through tools and representational systems built around human perceptual assumptions, the organism’s authentic contribution becomes indistinguishable from the structure of the apparatus. This outcome establishes the boundary of the translation and indicates the gap between what the system can present and the organism’s actual perceptual world.

Since the system constructs a reality inseparable from the organism’s signal, the study requires an analytic method to address the generative role of perception and instrumentation; this is the epistemological function of phenomenology. Phenomenology, as articulated by Edmund Husserl,2 approaches lived experience as a legitimate domain of inquiry with its own investigative protocols, instead of reducing conscious experience and mental phenomena to neurophysiological processes, as empirical science tends to do. Within this framework, (1) perception is understood as a generative process, one that organizes sensory flux into coherence and turns encounter into intelligible form; and (2) reality is understood as something generated through perception, as a field of meaning that takes form through the ongoing work of seeing, touching, and making sense of what is encountered.

Phenomenology, in this sense, defines a structure for thinking about the generative practice of rendering data into visual form. The tools I use operate as perception-making systems in a process distributed across technical and biological thresholds. In doing so, they participate in constructing the very conditions of perception, setting the parameters of what can appear, what registers as signal, and what remains outside the frame of intelligibility.

Applied to this context, the multiple mediations mentioned earlier in relation to generative art (as well as the additional ones that appear when the signals come from a non-human body) appear as successive sites where experience is constituted, where each layer perceives in its own way: the sensor reads a pulse, the algorithm interprets a waveform, the visual system arranges it into form, and the observer completes the circuit by finding meaning. Together they build a shared field of perception in which experience is collectively produced across human and non-human thresholds. We can, therefore, see this process as generative and unsettle the assumption that mediation is inherently obstructive, shifting the question from “How do we reduce interference?” to “What kind of perceptual reality takes shape through interference itself?” The system, after all, does not reveal the “true” signal behind the data but constructs worlds of relation and visibility through the conditions it sets.

3.2 Situated Knowledge and Epistemic Constraints

Following the recognition that the system constructs worlds of relation and visibility through its constraints, we must next examine how knowledge forms and becomes authoritative within these computationally-produced frames. In science and technology studies, Donna Haraway and Bruno Latour both address this in different ways.3 Haraway describes how scientific practice often isolates a phenomenon from the relations that sustain it, detaching it from contingent conditions and recoding it as discrete, comparable data. The result is knowledge that appears universal because it has been stripped of the particular circumstances that produced it.4

Latour approaches the issue by describing how scientific facts result from a chain of transformations.5 In Pandora’s Hope, he documents how soil scientists move from the forest floor to the laboratory, and convert the site into samples, measurements, and inscriptions. Each step alters what can be carried forward: local conditions are removed, classificatory order is added, and the resulting data reflects the constraints of the procedure rather than the full complexity of the site. Latour frames this as a trade-off between amplification and reduction, in which analytic control is gained while elements that cannot pass through the transformation are excluded.

Both critiques target the same assumption: what Thomas Nagel called the ‘view from nowhere’,6 the belief that observation can originate from a position outside the situation it describes. Haraway responds to this illusion with the framework of situated knowledge, which returns inquiry to the conditions that make it possible.

The necessity of situated knowledge takes on particular weight when the observer and the observed occupy fundamentally different perceptual frames, as is the case in the study of animal communication. Much of this field still follows what linguists call the code model: communication conceived as the transmission of information between discrete subjects. Within this framework, vocalizations that don’t trigger measurable behavioural changes or gestures that lack statistical regularity get classified as noise or aberration. We presume human language carries meaning even when we don’t understand a particular utterance, while demanding that animal communication prove its significance through empirical demonstration each time.

The question, “What are they trying to tell us?”, already imposes assumptions of intention and semantic content modeled on human speech. A more rigorous analytical approach focuses instead on the relational dynamics of signals: specifically, patterns of recurrence, contextual dependency, and temporal adjustment. Recent work utilizing machine learning is moving in these directions, and while computational methods have their own biases, they successfully identify structures overlooked by conventional analysis. Interestingly, irregularities frequently dismissed as noise prove to be the most organized and generative components of the communicative event, structures the code model entirely failed to capture.

4. Algorithmic Mediation and Animal Umwelten

This break from reliance on human linguistic models defines the primary function of algorithmic processing in this context, offering a specific utility for bypassing anthropocentric cognitive habits. Deep learning systems identify behavioural structures invisible to human researchers simply because the software approaches data without the requirement of semantic anticipation. This absence is nevertheless limited, because these systems still encode prior structure in their architectures, objective functions, preprocessing pipelines, and sensor configurations, so their openness is relative to human linguistic expectations rather than a neutral position. Where traditional methodologies demand an a priori decision about which calls or gestures warrant measurement, computational systems ingest datasets large enough for correlations to surface independently. The model registers organizational forms outside our linguistic templates because it does not begin with a hypothesis about the architecture of communication.

4.1 Algorithmic Mediation in Marine Bioacoustics

We see this capacity concretely applied in the continuous acoustic surveillance of marine environments. Hydrophone arrays now record soundscapes on a massive scale, producing volumes of data that no human team could manually analyze. The 2024 work by researchers at MIT and the CETI project7 illustrates this. They applied machine learning to sperm whale recordings, tasking the system with detecting statistical regularities without predefined categories.

The study identified a communication system built from codas: sequences of clicks organized by rhythm and precise timing, where differences can consist of a single additional click, a small change in tempo, or a longer pause. To the human ear, these variations appear as noise or acoustic inconsistency, yet, the deep learning algorithms, processing the sheer volume of examples simultaneously, identified these seemingly random features as systematic variations cohering into a sophisticated structure.

Decades of cetacean research failed to grasp this complexity because the operative analytic framework sought a one-to-one correspondence between sound and meaning, listening only for calls that repeated identically. Sperm whale vocalizations resisted that model because their signals are highly variable and context-dependent, but the machine learning analysis, thanks to its continuous modulation organized by relational difference, suggests that those variations themselves carry the information. The communicative content turns out to reside in the micro-adjustments between signals, not in the signals as fixed units, which is a logic we could not detect because we looked for a pattern modeled on human exchange, while the algorithms succeeded exactly because they lacked that specific constraint.

While this algorithmic analysis successfully identifies the organized structure of sperm whale communication, it does not resolve the fundamental problem of subjective access. The algorithms cannot translate the meaning of the codas into human-language equivalents, but what they can do is adjust the angle of situatedness for human inquiry.

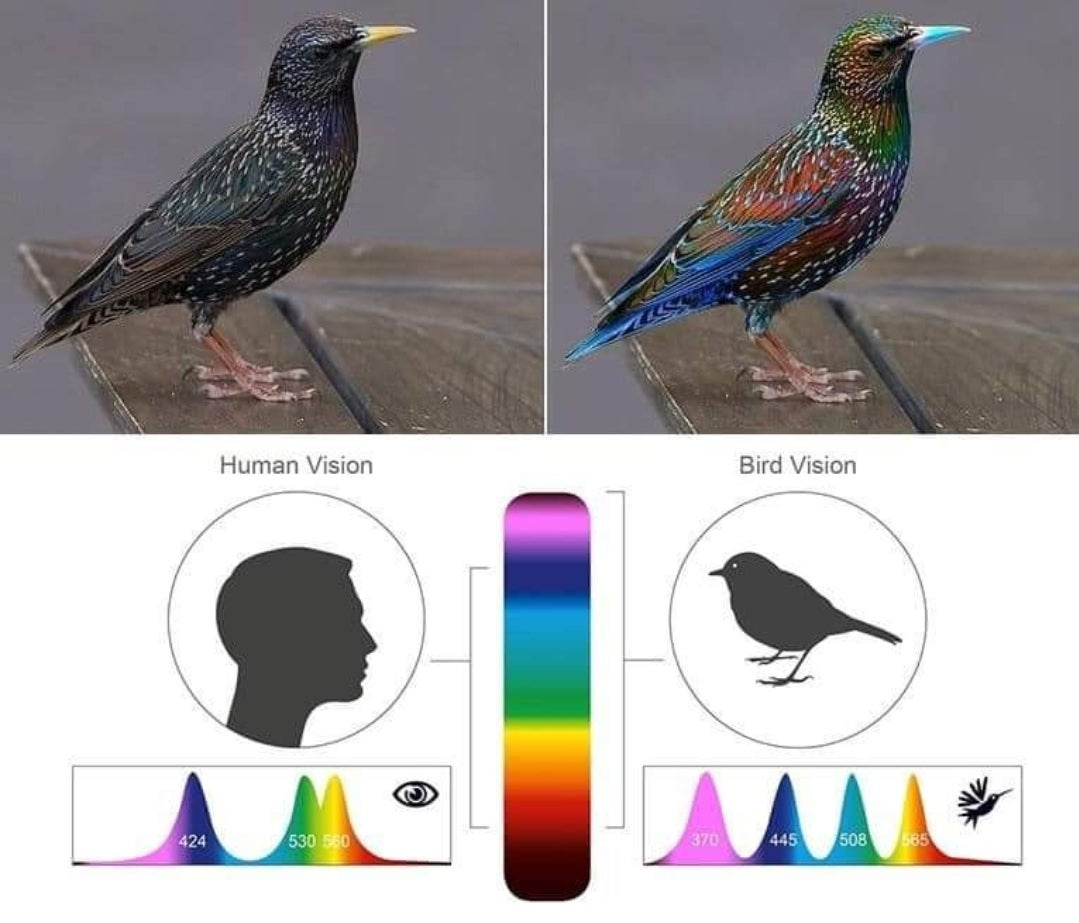

To understand this limitation, we must first acknowledge that every species perceives a radically different version of reality. For the sperm whale, the world is defined by acoustic maps traced through reflected sound, a process occurring across vast, volumetric distances in water. For a bat, the world is made of echoes, not images, and its sensing is optimized for short-range, high-frequency detection in air. For a bee, the world is structured through ultraviolet patterns that our eyes can’t register. A starling, with a critical flicker fusion frequency (CFF) of approximately 120 Hz8 (almost twice the human threshold of 60 Hz) perceives time at a faster rate, causing what seems continuous to us to appear as rapid pulses. Cephalopods sense light across their entire integument, with their skin itself functioning as a photoreceptive surface.

Each organism exists inside its own perceptual range, and that range defines the kind of world it can inhabit. We, in turn, are constrained by our own narrow bandwidth: we see light between 400 and 700 nanometers and live surrounded by a constant field of activity we cannot detect, as our devices, cameras, microphones, and sensors are all built around these human thresholds.

This leads us to the concept of the Umwelt. Introduced by biologist Jakob von Uexküll,9 Umwelt describes how each species inhabits a unique version of reality generated by its perceptual system. Thomas Nagel explored this epistemological barrier in his 1974 essay What Is It Like to Be a Bat?,10 asking what it would mean to access another being’s first-person perspective. As mentioned, the bat inhabits a phenomenological field organized by echolocation instead of vision, and, concretely, this means we cannot step outside our perceptual constitution to access the bat’s.

The sperm whale also utilizes sound as its primary modality (echolocation), just like the bat, but unlike the functional separation seen in species like the bat, for the whale, the acoustic signals that construct precise maps through reflected sound waves are simultaneously the signals through which social relations become perceptible. Perception and communication are one, single constitutive process. This functional integration means that any attempt to understand whale vocalizations without reference to their spatial and navigational function fundamentally misrepresents the nature of the communicative act itself.

The computational method applied to the whale study11 delineates the perimeter of Nagel’s problem. While statistical models register recurring temporal and relational configurations across large sets of clicks, operating at a resolution that exceeds human hearing, this success demonstrates the existence of an internal order detectable by non-human-modeled systems. All of this operates as what might be called a technical Umwelt-bridge: a system capable of registering non-human-scale regularities. This finding, however, simultaneously reinforces the nature of the epistemological limit: the algorithm detects structure, but it cannot access the structure’s felt content. Beyond the boundary of direct human experience lies a structured system of non-human perception whose qualitative texture remains inaccessible.

4.2 Reflexive Perception and the Human Umwelt

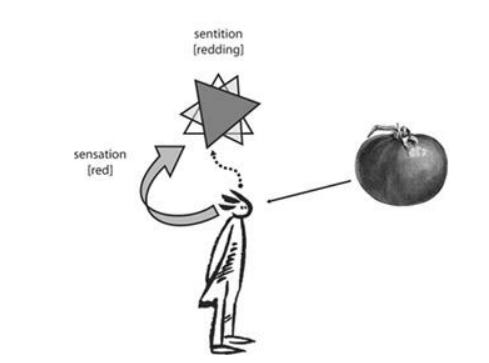

The epistemological barrier we encounter when attempting to understand non-human perception applies equally to the generation of our own perception. We can describe neural activity in comprehensive detail. We can trace how photons striking the retina trigger cascades of electrical signals, how these signals propagate through the visual cortex, how specific populations of neurons respond to edges, motion, color. What we cannot explain is why this neurophysiological activity produces the lived quality of seeing red, the felt texture of pain, the particular character of any conscious state. David Chalmers termed this the hard problem of consciousness12: the gap between objective description and subjective experience. What philosophers call qualia, the intrinsic feel of experience, remains outside the scope of functional explanation. You can specify every neural mechanism involved in color perception without accounting for why those mechanisms generate the phenomenal experience of redness.

Nicholas Humphrey13 proposes that this qualitative dimension arises through a specific cognitive operation he calls “redding.” When light from a tomato stimulates photoreceptors, the brain produces an internal response. It then monitors its own response and attributes that self-generated activity to the external object. As Humphrey writes, “the magic of your phenomenal sensation... is rubbing off onto the things as such.” The redness appears to reside in the tomato, but phenomenologically it is the point where the skin of the eye meets the surface of the world. What we experience as an objective property of things turns out to be the externalized signature of our own perceptual machinery. The process works by concealing itself. Color feels like it belongs to objects because perception projects its own activity outward while erasing evidence of that projection.

If perception works by projection, then we cannot treat our own awareness as a fully observable target. Perceiving cannot step outside its own activity to examine itself. When perception becomes both the instrument and the object of analysis, the distinction collapses, and the investigation returns to the act of perceiving rather than to an independent mechanism available for inspection. We are left not with a stable observer looking at a stable world, but with a recursive loop where the position of the subject begins to dissolve. The interpretive barrier attributed to non-human Umwelten exemplifies a more general condition: perceptual processes, human or otherwise, do not disclose their own operations to the agent whose experience they generate.

There exists an intuition that consciousness achieves its purest form in moments of sustained stillness; for instance, lying awake in darkness and noticing the flicker of the visual field, or pressing on closed eyelids until geometric patterns begin to form from within the eye itself. As if reducing external stimuli might allow us to see the mechanism of awareness operating unmediated, we tend to imagine these instances as direct encounters with perception stripped of interpretive overlay. However, what becomes apparent is a reorientation in how perception organizes itself, since the more deliberately attention focuses on the bare event of seeing, the less stable the perceiving position becomes. Phenomenal experience continues, but the organizing “I” that typically anchors these experiences to a stable observing position loosens its structure, as if becoming diffuse. What remains is perception as a field of experience that generates itself without requiring a fixed center from which it emanates, without needing the anchoring presence of a perceiver to claim ownership over what appears.

In The Visible and the Invisible, Merleau-Ponty14 reformulated this paradox through materialist terms, arguing that the seer and the visible exist in a relationship of mutual constitution rather than hierarchical separation, where each exists within what he called “the flesh” of the other, a formulation that refuses the clean separation between observer and observed. The concept introduced above through Humphrey’s account of “redding” in Soul Dust15 expresses the same idea as this, in that perception operates through participation rather than possession, through a kind of mutual involvement that makes it impossible to say where the perceiving body ends and the perceived world begins. The eye participates in bringing that world into perceptual being through its own material presence, through the specific constraints and affordances of its structure.

A useful illustration of this structural problem in perception comes from a familiar visual event: the appearance of floaters (muscae volitantes). These small specks, which seem to move slowly across the visual field, are in fact clumps of collagen fibers and cellular debris suspended in the vitreous humor that cast faint shadows onto the retina. This physiological event compels attention because it materially illustrates the collapse of the boundary we assume separates the observer from the observed. The mechanism that enables us to perceive the external world simultaneously inserts its own internal, material presence into what appears. The floaters are the perceiving apparatus making itself visible through the act of perception. The boundary assumed to block transparent vision paradoxically reveals the apparatus itself through a recursion where sight apprehends its own physiological process. In attempting to perceive outward, the subject encounters its own materiality, and in that encounter, the separation between subject and object is rendered unstable.

Other perceptual phenomena, especially those extending past optical materiality into neurological processing, confirm that what we experience as stable vision results from constant processes of reconstruction that remain invisible to conscious awareness. One illustration of this occurs with phosphenes, the luminous shapes that appear without any external light, for instance when pressure is applied to closed eyes and the mechanical stimulation of the retina excites the same photoreceptor cells that ordinarily respond to photons. This excitation makes the brain generate visual patterns such as circles, grids, or flashes that exist within the visual cortex. In this situation, the visual experience, independent of external input, activates its own pathways and produces a self-generated interpretation of neural activity.

A related principle appears in the “waterfall effect,” where prolonged observation of motion causes the stationary visual field to seem to move in the opposite direction. For example, after watching downward motion for an extended period, stationary objects may appear to move upward. This phenomenon evidences temporal plasticity in visual processing, thanks to the perceptual system’s ability to continually recalibrate itself through comparison and correction, which is a process that occurs beneath conscious awareness.

Sensory aberration in these cases exposes the necessary condition for coherent vision. Coherent visual experience is actively put together through processes that must remain invisible and unnoticed in order to function. The system works by concealing its own operations; the moment we become aware of these operations, as demonstrated by the phenomena of phosphenes and the waterfall effect, we are witnessing the machinery itself rather than its ordinary output.

Our own perceptual system is therefore another Umwelt: a self-organising, self-concealing field that cannot make itself fully transparent to itself. If our access to animal Umwelten is structurally limited, and our access to our own perceptual operations is equally limited, then it is inconsistent to grant ourselves a position of full transparency while denying it to other species.

5. Witnessing Without Claim as an Ethical Frame for Translation

The physiological feedback loops described above demonstrate that a “neutral observer” position is biologically impossible. The subject remains structurally involved in the act of seeing, and every measurement imports the parameters of the apparatus. The resulting data depend on those parameters for their form, while the operations that produce that form remain largely unrepresented. In work with non-human biosignals, if distortion cannot be removed, we need an explicit account of the stance from which the data are read.

5.1 Intentionality and Directional Aim

The concept of intentionality, derived from the Latin intendere (”to aim toward,” “to stretch toward”), describes how mental representations work: they are about something, they point toward an object. When you perceive a red tomato, you form a representation that aims toward “redness” as its intentional object, even though the physical stimulus is actually a wavelength of light. The representation points beyond the material source to qualities that exist in your perceptual experience.

Approaches to biosignal translation typically operate through this intentional structure. The analyst forms a representation of the signal that aims toward the organism’s internal state as its intentional object. A spike in heart rate is represented as pointing toward “stress” or “arousal”; a vocalization is represented as pointing toward “alarm” or “mating intent.” Following the terminology introduced above, the signal functions as X (the real-world source), while the inferred psychological state functions as Y (the intentional object the representation aims toward). This is the first type of stance: one that reads through the signal to reach the organism’s subjective condition, treating the data as an indicator of states that exist independently of the measurement apparatus.

When this intentional framework is applied to computational analysis, the pipeline operates through the same extractive logic. Signals undergo segmentation and normalization before being reduced to features that correspond to predefined behavioural categories, such as contact calls, territorial displays, affiliative interactions, etc. These categories function as the intentional objects toward which the computational process directs itself, since the system is configured to detect their presence and to classify input accordingly. What results is output structured by the operational parameters of the model: the features selected for extraction, the training corpus used for learning, the classification boundaries established by the algorithm. Such output is interpreted, however, as direct evidence of the animal’s internal psychological states, as though the apparatus had succeeded in aiming through the material signal to access the subjective reality presumed to generate it.

5.2 Relationality and Inferential Suspension

A generative system benefits from a different design approach, one that treats input signals as received within defined constraints rather than as transparent indicators of hidden psychological content. The challenge is to establish a technical environment that allows signals to be recorded in a reliable and interpretable manner while accounting for the limitations of the device. Where the intentional stance aims through the signal toward the organism’s subjective states, this stance stops at the signal itself and examines how it is constructed by the apparatus.

To define this second stance, I use the term “witnessing without claim.” This framing contains terms presented as an alternative set of vocabularies that can help us think through what a non-extractive analytic stance might require, and it is informed here by Sufi epistemological concepts that address the relationship between perception and the position of the perceiver. Within Sufi intellectual traditions of the 12th and 13th centuries, particularly the Andalusian school associated with Ibn ʿArabī,16 practitioners developed epistemological frameworks to describe states of consciousness where the boundaries between observer and observed become less fixed. These terms described specific cognitive and perceptual configurations that practitioners could train themselves to inhabit.

Unlike most phenomenological accounts, which remain primarily descriptive, these Sufi frameworks are articulated as practices for tuning attention and conduct: they specify how to adopt particular perceptual stances and how those stances constrain what one is permitted to claim about what is perceived. They also link epistemology to ethics in a direct way, treating modes of knowing and obligations toward what is known as a single problem rather than separate domains. It is this coupling of trained stance and ethical constraint that I import here, rather than any doctrinal content.

One such term is shuhūd (شُهُود, witnessing), which describes perception that proceeds without a fixed ego assigning ownership to what is observed.17 When applied to data work, shuhūd operates as a methodological approach where the focus is on the structural properties produced, and the data are not treated as indicators of an animal’s interior states, allowing the data to be handled strictly as the product of the recording system and its procedures.

Another term, fanāʾ (فَنَاء), clarifies the positional dimension of this stance. The term has long-standing usage in Sufi writing, employed within a broader account of relational perception in which the assumption of a self-sufficient subject is suspended. In everyday Arabic, fanāʾ denotes an open courtyard or entry space; etymologically, it derives from the root f–n–y (ف ن ي), associated with the meaning of annihilation, perishing or passing away. The concept names a state where the practitioner relinquishes the claim to be a stable center from which perception radiates. In this study, fanāʾ provides a structural figure for an analytic posture in which the system does not assert a singular vantage point but maintains a vacated and open operational field where non-human signals register according to the relations produced within the technical configuration.18

A third term, ḥaqq (حَقّ), gives this posture its ethical weight. Ḥaqq means both “Truth” and “Right.” Every existent being has its own ḥaqq: a fact of presence and a due. In the present context, to acknowledge the ḥaqq of another organism is to recognize that its modes of appearing have a standing independent of human interpretive projects, and that its signals are not raw material awaiting our meaning. Such signals are already structured, already coherent within their own operational domain. Truth, on this view, involves giving each being its due, which in this context can be understood as allowing its signals to retain a degree of independence from human interpretive schemes.19

5.3 Practices of Perceptual Re-Calibration

The recalibration I’m proposing through computational means has parallels in somatic practices that train bodily attention to non-human patterns. Among the Runa people of Ecuador’s Upper Amazon, shamanic practice involves ritual transformation into jaguar form, which Eduardo Kohn documents as a deliberate technique for training perception according to predator logic.20 For the shaman, this requires systematically attending to the cues that organize jaguar perception, including movement patterns in dense forest, acoustic cues used in low-light conditions, and the temporal routines of nocturnal activity, and using these cues to adjust their own sensory focus toward the environmental conditions that structure jaguar behaviour.

Comparable approaches appear in contemporary multispecies and enactive research. Myers’s “Becoming Sensor” work, for example, employs movement exercises in which participants follow plant growth trajectories, adjust pace to insect locomotion, or modulate breath to environmental rhythms.21 Related techniques in movement anthropology and ecological practice, including Ingold’s work on movement and correspondence22 and Tsing’s analyses of multispecies attunement,23 involve tracing migration routes on foot or engaging with the temporal cadences that shape an organism’s interaction with its surroundings. These methods treat the body as a perceptual instrument configured to register the temporal and spatial structures through which another organism constitutes its world. As practitioners approximate aspects of another species’ perceptual organisation, knowledge develops through this situated participation (in contrast to detached inspection) without the need to claim access to its subjective states.

Machine learning provides a technical analogue to these somatic and contemplative practices. As discussed in the earlier section on algorithmic de-centering, these systems process datasets according to the statistical relations present in the signals themselves, recording dependencies and recurring structures before any human-defined schema is applied. The computational method applied to sperm whale codas,24 for instance, succeeded in identifying systematic variations precisely because it did not require signals to conform to predetermined linguistic categories, registering patterns of continuous modulation that decades of traditional cetacean research had classified as noise or inconsistency. Both the Runa practice and machine-learning techniques involve recalibrating the apparatus, bodily or computational, so that it can respond to patterns that fall outside human expectations.

The technical apparatus, like the trained body in the shamanic and multispecies movement practices described above or the disciplined attention in Sufi contemplative work, functions as what was earlier termed a technical Umwelt-bridge: a system capable of registering non-human-scale regularities while acknowledging that this registration does not provide access to the felt content of the experience.

6. Design Conditions for Biosignal Translation Systems

For biosignal translation, “witnessing without claim” establishes three practical requirements for system design.

Transformational traceability.

Each layer of processing must remain visible as a design choice. Sensor placement, sampling rate, feature construction, training data selection, and model architecture are treated as active conditions that determine what can appear in the output. For any regularity that is reported, it should be possible to specify which combination of these operations made it available to the system as something that could be detected.Umwelt-specific scope.

The system is understood as constructing a technical Umwelt, a restricted field of cues and dependencies that can function as carriers of significance for the model. Claims are confined to the organization that holds within this constructed field. A model that clusters whale codas, for example, demonstrates that a stable pattern exists under a particular representation, feature set, and training regime. It licenses statements about regularities in the signal under those constraints. It provides no basis for assertions about semantic meaning, communicative intention, or qualitative experience.Mode-of-coupling description.

The form of coupling between organism and apparatus must be specified as part of the result. Systems that process archived recordings, interactive setups that respond to live input, and somatic methods that train bodily attention each realize different relations to the signals they register. Interpretive claims are tied to this mode of coupling and are read as properties of that specific configuration.

These requirements define a controlled scope for inference that makes non-human activity analytically accessible while respecting the epistemological limits of the apparatus. Their concrete implementation in specific technical systems, including the design of logging mechanisms for transformational traceability, evaluation metrics for Umwelt-specific scope, and documentation protocols for mode-of-coupling, remains to be developed in future work.

7. Conclusion

This study set out from a practical problem in generative art: what happens when biosignal translation systems, originally built for humans, are applied to non-human organisms. The analysis showed that these systems construct a constrained field in which some forms of activity become legible and others disappear. Phenomenology, situated knowledge, and the concept of Umwelt were used to describe this construction. The sperm whale case and Humphrey’s account of perception demonstrated that neither machine learning nor neuroscience can bridge the gap between structural description and subjective experience. What these methods accomplish is making structural regularities detectable at scales and resolutions previously inaccessible to human observation.

The study proposed witnessing without claim as an alternative stance for working with non-human biosignals. The stance directs attention to how apparatus design, model configuration, and interpretive habits determine what can appear as meaningful. The Sufi concepts of shuhūd, fanāʾ, and ḥaqq supplied a vocabulary for this posture: attending to structure without ego-possession, relinquishing the assumption of a central observational vantage point, and acknowledging that other organisms have modes of appearing independent of human projects of understanding.

Three design conditions operationalize this stance. Transformational traceability requires that each procedural layer remain visible as an active determinant of output structure. Umwelt-specific scope confines claims to the organization detectable within the technical field constructed by the apparatus. Mode-of-coupling description specifies the relation between organism and system as part of any reported finding.

The methodological framework has implications across computational ethology, bioacoustics, animal-computer interaction, multispecies design, and creative technology. In classification systems, it suggests moving from psychological attribution to structural description. In system evaluation, it establishes criteria for assessing whether designs respect the epistemic limits inherent to cross-species work. In generative practice, it provides conceptual resources for building systems that acknowledge their role in constituting what appears.

This framework has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the design conditions proposed in this study are methodological principles rather than implemented technical systems; their translation into concrete protocols, evaluation metrics, and documentation practices requires further development. Second, while I draw on Sufi epistemological concepts to articulate an alternative stance, these terms are imported analogically as conceptual resources for thinking about perceptual discipline rather than as claims about mystical experience. Third, the framework does not solve the access problem it describes; it proposes a disciplined way of working within that limitation rather than transcending it. The extent to which this stance mitigates anthropocentric projection in practice depends on empirical validation across diverse technical implementations, organism types, and modalities of signal capture. Such validation would need to assess not whether the stance eliminates interpretive mediation (which remains structurally impossible), but whether it produces analytically stable results that maintain traceability to their apparatus-specific conditions of production.

The stance proposed here accepts the epistemological problem of accessing non-human subjective experience as constitutive of the problem domain and builds methodological discipline around it. The systems examined extend what humans can detect in non-human activity from within human-built operational parameters. The objective is to construct interfaces and analyses that register non-human organization as structured and consequential, recognizing that claims about the phenomenal character of inhabiting those patterns lie outside what these apparatuses can deliver.

Future work might explore how these principles apply to specific contexts, such as interactive installations responding to live animal signals, participatory design processes involving animal subjects, or evaluation frameworks for assessing anthropocentric bias in existing animal-computer interaction systems.

Lisa Gitelman, “Raw Data” Is an Oxymoron (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013), 2.

Edmund Husserl, Ideas Pertaining to a Pure Phenomenology and to a Phenomenological Philosophy, trans. Fred Kersten (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1982), 48.

Donna J. Haraway, “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective,” Feminist Studies 14, no. 3 (1988): 575–599; Bruno Latour, Pandora’s Hope: Essays on the Reality of Science Studies (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999), 24.

Haraway, “Situated Knowledges,” 579–585.

Latour, Pandora’s Hope, 24–32.

Thomas Nagel, The View from Nowhere (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986); Donna J. Haraway, “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective,” Feminist Studies 14, no. 3 (1988): 584.

David F. Gruber et al., “Contextual and Combinatorial Structure in Sperm Whale Vocalizations,” Nature Communications 15 (2024): 2.

Jannika E. Boström et al., “Ultra-Rapid Vision in Birds,” PLOS ONE 11, no. 3 (2016): e0151099; Lydia M. Mäthger, Steven B. Roberts, and Roger T. Hanlon, “Evidence for distributed light sensing in the skin of cuttlefish, Sepia officinalis,” Biology Letters 6 (2010): 600–603.

Jakob von Uexküll, A Foray into the Worlds of Animals and Humans, trans. Joseph D. O’Neil (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010).

Thomas Nagel, “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?,” The Philosophical Review 83, no. 4 (1974): 436

Gruber et al., “Contextual and Combinatorial,” 3.

David J. Chalmers, “Facing Up to the Problem of Consciousness,” Journal of Consciousness Studies 2, no. 3 (1995): 200–219.

Nicholas Humphrey, Soul Dust: The Magic of Consciousness (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011), 41–42.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty, The Visible and the Invisible, trans. Alphonso Lingis (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1968), 130–155.

Humphrey, Soul Dust, 86.

William C. Chittick, The Sufi Path of Knowledge: Ibn al-‘Arabī’s Metaphysics of Imagination (Albany: SUNY Press, 1989); Michael Sells, Early Islamic Mysticism (New York: Paulist Press, 1996), 275.

Ibn al-‘Arabī, Futūḥāt al-Makkiyya, excerpts trans. in Chittick, Sufi Path of Knowledge; Alexander Knysh, Sufism: A New History of Islamic Mysticism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017), 133.

J. Milton Cowan, ed., The Hans Wehr Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic, 4th ed. (Urbana, IL: Spoken Language Services, 1994), 852; Annemarie Schimmel, Mystical Dimensions of Islam (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1975), 59–60.

Chittick, Sufi Path of Knowledge, 129.

Eduardo Kohn, How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology Beyond the Human (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), 94.

Natasha Myers, “Becoming Sensor in Sentient Worlds: A More-than-natural History of a Black Oak Savannah,” in Between Matter and Method: Encounters in Anthropology and Art, ed. Gretchen Bakke and Marina Peterson (London: Routledge, 2017), 73–96.

Tim Ingold, Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description (London: Routledge, 2011), 12.

Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015), 21.

Gruber et al., “Contextual and Combinatorial Structure,” 4.

Incredible work